Fat Tailed Thoughts: The Future of Finance is Embedded

Embedded sells us finance products right as we're making other purchases, precisely when we need it. Tech and financial services will partner to make it the future.

Hey friends -

Most of these letters revolve around financial services companies - the old ones, the slow ones, the new ones, and the big ones. But despite my enthusiasm and all of the interesting work they do, on the surface it seems they're increasingly becoming a sideshow.

It seems every company is becoming a financial services company. Products like loans and payments are no longer a separate consideration - they're embedded directly in the products we use. Use Affirm's buy now, pay later to purchase your new couch. Buy that influencer's bracelet without ever leaving Instagram.

It's the world of embedded finance.

In this week's letter:

Embedded finance: everyone's a fintech or at least pretending to be, the Durbin Amendment and other arbitrages, and where embedded finance goes from here

Over 40% of banks are still "exploring" cloud, giant cyborg cockroaches, and other cocktail talk

An attempt to find a use for the last dregs uncovered an awesome cocktail, The Devil's Soul

Total read time: 14 minutes, 3 seconds.

Everyone's a Fintech

I'll own up to it. I'm now one of those people that orders their groceries.

I actually enjoy the mindless wandering up and down the aisles, but the prices at the local walking-distance grocery store have gotten out of hand. Surprisingly, it's now about 25% cheaper for me to order my groceries delivery from Whole Foods. I still make the occasional trip to the local store for essentials like hard-shell stand-and-stuff tacos that Whole Foods refuses to sell.

My grocery habits are neither here nor there. What struck me was the loan offer when I went to pay.

That was surprising. Citi, my credit card issuer, wants to sell me a low-rate monthly loan to finance my groceries. Interestingly, the bank won't sell me a similar loan for a $500 bouncy castle or a $37 inflatable unicorn pool floaty.

It wasn't even the only financial services offer on my way to checkout. Amazon first tried to sell me its branded Visa credit card. Then Citi tried to get me to pay with my rewards points. Only after I ignored the first two offers did Citi try to sell me a Hail Mary grocery loan. I navigated three offers just to buy my groceries.

These "purchase plus financial services" offers are increasingly the norm because they work. We, consumers, are buying them. And they can be enormously profitable for the sellers.

Embedded finance is more profitable than standalone

Executed correctly, embedded finance is more profitable than standalone.

Most financial decisions are not made in isolation, rather they're means to an end. We invest so we can buy more in the future and borrow so we can buy more now. We purchase insurance to protect against disasters that are top of mind because we just had a major life event or made a major purchase.

Amazon delivered those offers to me right at a decision point, on the checkout page of my grocery purchase. The Amazon credit card signing bonus could have fully offset my purchasing cost "this purchase could be $0.00!" The Citi loan could have allowed me to defer most of the payment for months. I won't go out of my way to explore financing for groceries but, right at the point of purchase, I considered it.

It's a huge competitive advantage to be able to offer financing right at purchase. Car dealerships have been doing it for decades. Much more recent buy now, pay later point-of-sale lenders underwrote almost $100 billion of e-commerce purchases in 2020, 2.1% of all purchases, a percentage that's projected to double by 2024. It's a rapidly maturing market. Affirm is now a public company and partners with companies like Apple to offer 0% APR loans to iPhone purchasers. Square acquired Afterpay for $29 billion and can deliver the loans everywhere Square is used.

Point-of-sale purchase financing is often small, but other embedded financings can be much larger. Startup Safely Finance finances something entirely different - moving costs. Through their property manager, renters can obtain as low as 0% APR loans to finance $30,000 of moving costs including their safety deposit, first and last month's rent, and more. Toast, a Square competitor, underwrites restaurant loans up to $250,000.

In each of the financing examples, the lender has an asymmetric data advantage that tilts the odds in their favor. Square and Toast see minute-by-minute cash flows for their customers, intimate details that allow them to underwrite at competitive rates. Affirm sees millions of shoppers' purchasing behavior, far more than any bank ever could. Safely Finance benefits from deep relationships with the property managers.

The lenders combine that advantage with two other innovations - modern technology and a seamless user experience. Older financial services companies are burdened by private data centers and processes that require significant manual intervention. Modern lenders complete the same processes with code that runs in public clouds. Not only is code better for experimentation and faster to run, but also the costs are almost entirely variable. The new lenders have an operational cost advantage.

Seamless user experiences supercharge embedded financing. Consumers can complete purchase loans in a click - they're not redirected to some unknown third party on a different website where they're forced to reenter all their data. Every step in selling a product is a chance for someone to back out. A single-click checkout has a massive conversion advantage over more complex experiences.

Embedded lending is just one type of embedded finance. Intuit Quickbooks offers a 1.00% APY checking account bundled with your accounting software suite. Divvy, an expense management startup bought by Bill.com sells Divvy branded credit cards. Every airline and travel booking company imaginable sells travel insurance.

We've become so accustomed to these financial services offers that they've become almost expected. Gone are the days when banks sold checking accounts and insurance companies sold insurance. Now tech companies do both.

Or do they?

Everyone's a fintech (just don't read the fine print)

Most startups are not financial services companies. They don't have the competencies to risk score customers for anti-money laundering or the licenses to process payments. There's a long list of financial services "stuff" they don't do.

What they do is partner. It's the embed in embedded finance.

Divvy? Cross River Bank issues a card on the Visa network that Divvy white labels. Travel insurance? Probably Allianz or AIG underwriting the policy behind the scenes. Quickbooks checking account? Green Dot Bank.

Most startups don't offer the financial services themselves. They "rent" the capabilities, wrap them in a data advantage with a great user experience, and cross-sell them at key decision points. That division of responsibilities between tech and financial services - between unregulated and regulated - unlocks massive opportunities for startups and financial services companies alike.

Durbin Amendment and Other Arbitrages

The competitive moats around financial services firms are rapidly eroding. Banks for instance are structurally disadvantaged with costly regulation and legacy systems, yet they have a handful of unassailable advantages that no amount of innovation or venture capital money will diminish. In particular, they are slow, have a low cost of capital, and can offer products that unregulated companies cannot. We could explore similar structural advantages for insurers (float), money services businesses (flow of funds), and others, but for the sake of brevity we'll focus on banks.

Slowness is an advantage for banks

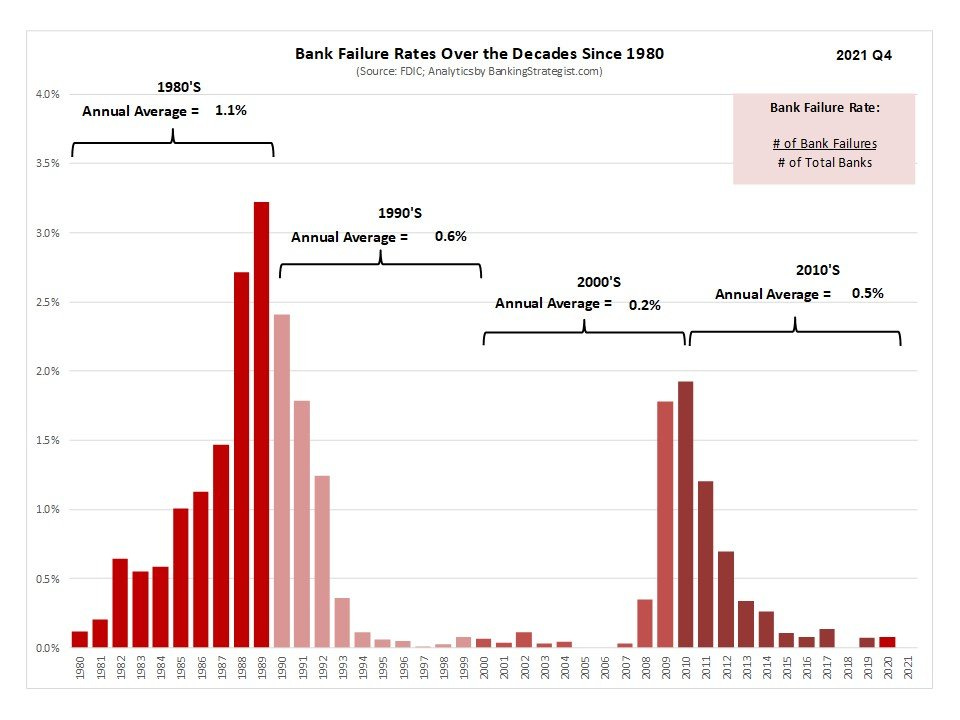

Banks are slow to change, often painfully slow. That's in part because they're conservative. Regulations require that they be profitable and maintain huge capital reserves in case of emergency, two requirements that hinder growth. Slowness means they can't expand as quickly, but it also means they'll be around when the going gets tough. In the US, 50% of small businesses fail by their fifth year, but less than 1% of banks close their doors annually.

Slow and conservative allows banks to optimize for services that startups can't offer and vice versa. Acquiring millions of users is a great startup problem - spend lots of money upfront and hope that the users stick around. Most of the startups will fail but a couple will survive at a tremendous scale. That's not a good model if you intend to service a user for 30 years like in the case of a mortgage. Slow and steady is a better fit.

Partnered together, a startup and a bank can create a mortgage product that neither can alone. The startup can collect your information just once, force banks to compete for the best terms, and create an easy-to-use interface to facilitate mortgage payments. The winning bank can ensure that you keep dealing with the same lender for the entire 30 years even when the startup is acquired or goes bankrupt.

It can be a valuable partnership. The numbers don't lie - banks now originate just 32% of mortgages in the US.

Slowness is a weird advantage that becomes more readily apparent when you consider venture capital returns. A venture capitalist builds a portfolio of companies with the expectation that most will fail, a handful might break even, and just one or two will create outsized returns. Done right, those one or two winners compensate for the losses in the rest of the portfolio many times over. It's a model designed for home runs, not singles and doubles.

A venture capitalist will generally only fund businesses that have the potential to be a home run. Once invested, the investor will often encourage rapid growth with associated high expense rates even if the startup could improve its probability of surviving by growing slower. A "just survive" outcome is not much better for a startup investor than a total failure. It's better to take a shot at a home run.

Banks produce steady, consistent returns over decades - they're a singles-and-doubles business model that venture capital doesn't fund. It means they can optimize for opportunities - like 30-year relationships - that startups simply cannot.

Deposits are near-zero cost of capital for banks

Banks also have capital advantages. While the average cost of capital for banks generally is 10.5%, deposits are about as close to zero-cost as can be found anywhere. A near-zero cost of capital allows banks to hypothetically lend at highly competitive rates. A bank can only exploit that advantage if it can attract deposits and identify opportunities to lend.

Here again, startups and banks can achieve together what neither can alone. A startup can focus on the marketing funnel - acquiring customers with mobile banking, spend management, and other features that are difficult for non-tech banks to develop. Under the covers, the bank provides the actual deposit accounts and benefits like FDIC insurance. It's a win for both companies.

That same startup may also create lending products - powered by the bank again - that dually benefit from the bank's low cost of capital and data insights captured by the startup. Together, the bank and startup can offer lower-rate loans that are nonetheless more profitable because they're better underwritten.

Such partnerships have created an entirely new industry - the poorly named neobanks - which are not banks at all, just tech with bank partnerships. Some of these new entrants have become large very quickly. Three-year-old Mercury raised $120 million last year at a $1.6 billion valuation as a "banking stack for startups." Chime raised $750 million at a $25 billion valuation in October and was exploring a $40 billion IPO as recently as January. Powering both neobanks are little-known actual banks The Bancorp Bank, Choice Financial, Evolve, and Stride Bank. They're among a relatively small group of banks powering a much larger number of startups.

Burdensome regulations can be competitive moats

Banks are the only companies that can offer deposit accounts and debit cards. That's already a moat. The Durbin Amendment supercharged it for small banks.

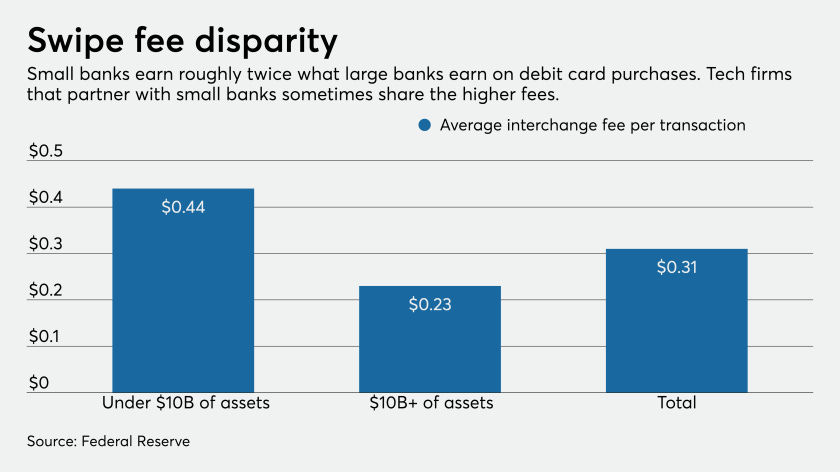

The Durbin Amendment, sponsored by US Senator Dick Durbin, is the source of one of the most astonishing regulatory arbitrage opportunities in recent memory. A cap on the interchange fees that banks can charge merchants on debit card transactions was buried in the 2011 Dodd-Frank Act. But the cap wasn't applied equally to all banks. Banks with more than $10 billion in assets have fees capped at $0.21 plus 0.05% per transaction. Banks with less than $10 billion in assets are exempted under the Durbin Amendment and can continue to charge pre-Durbin rates of up to $0.15-$0.20 plus 0.80%-1.05% per transaction. The resulting difference in the actual fees charged has been predictable.

That $0.21 differential may not sound like much, but it can make a world of difference. Banks and startups together can offer mobile banking that marries the best of a savings account with a slick user interface. A startup and a small bank can offer more - they can use the extra fees charged to the merchant to out-compete bigger banks. Chime uses the fees to fund customers receiving their paychecks early. Varo offers up to 6% cashback on debit card purchases. The Durbin Amendment probably wasn't created to help $25 billion Chime outcompete JP Morgan, but that's been its effect.

Dodd-Frank Section 1033 offers a similar opportunity if it ever gets implemented. It requires that consumers have the right to access their own bank account and transaction data in a usable electronic format. Said differently, consumers will be able to give any startup access to their bank account and banks will have to support it. There will almost certainly be a Durbin Amendment equivalent that exempts smaller banks - another arbitrage opportunity.

I expect more of these regulatory moats to emerge in time. Congress is currently debating if stablecoins should only be issued by banks. If such a proposal passes, it would open the doors to another regulatory-enabled bank-startup partnership model.

It's just one of the opportunities on the horizon for embedded finance. There are many more to come.

Embedded Finance Future

Embedded is the future for much of financial services. The advantages of embedded over standalone are simply staggering.

Embedded means putting an offer in front of a potential customer at a purchasing decision point rather than as an afterthought. Embedded means a seamless user experience that drives higher conversion rates. Embedded means more and better data to tailor offers.

Embedded means more financial products sold.

Gone are the days when the local banks and insurers had small-town monopolies. With it went the fat margins for converting dollars to francs. Hudson Valley Credit Union doesn't just compete with the local People's Bank, it competes with every bank and bank-like company that can get me to download an app on my phone.

Financial services companies aren't tech companies - and that's okay

Most financial services companies simply aren't technology companies. They may use technology internally to improve their products, but that doesn't make them technology companies. A tech company - tech startups in particular - have a different DNA. Anything that can be code, is code. Services are designed to support massive scale and be self-service whenever possible. Mobile-first is the default, not an afterthought.

That's okay. Financial services companies don't need to be tech startups. They can instead optimize for different advantages - products where stability and longevity are differentiators, identifying markets where they can lend against a low cost of capital, and designing products where regulations are barriers to entry.

Tech startups - for the most part - also don't need to be financial services companies. They can optimize for their own set of advantages rather than attempt to be something they're not. Buy now, pay later startups are just the beginning of problems ahead. I've been vocal in my disdain - building a company on other people's money doesn't teach underwriting discipline. Tech companies have core competencies. More often than not, financial services won't be one of them.

Partnering for embedded finance will be the most successful model

Partnering to embed financial services is where tech and finance can achieve the biggest wins. Each can bring to bear its own competencies and a business model appropriate for the service that's being offered without endlessly fighting a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde battle of hypergrowth and long-term stability and other similar inevitable internal conflicts.

Critically, separating the two allows startups to try and fail without undermining long-term financial relationships. That's a good thing. The cost of an insurer or bank failing is high - we want them to optimize for long-term stability. The cost of startup tech companies failing is low, we actually want them to fail. Failure means startups are experimenting with how traditional services can be delivered and consumed. It's not experimenting if there aren't failures.

There will be a handful of companies that manage excel at both tech and financial services. PayPal and Square immediately come to mind as relatively young companies. Column is a new technology-first federally chartered bank that seems poised to follow in their footsteps. From the older guard, JP Morgan stands out as unusually adept at marrying tech and finance.

But I pose that they are the exception, not the rule. Most of the 4000+ banks in the US will be better off partnering as will the countless insurance companies and lenders.

Financial services will consolidate, for better or worse

That will mean winners and losers - embedded finance will almost certainly lead to consolidation in many financial services industries. The handful of tech companies that survive will reach an enormous scale. They won't need thousands or even hundreds of embedded financial services partners.

I write that with mixed emotions. Reading the tea leaves and acknowledging the superiority of a partnership-based embedded finance model, I consider consolidation almost an inevitability. In the same breath, I know that will mean that my local bank will likely go the way of my local bookstore. Local banks can be the lifeblood of towns, but I'm realistic that I now frequent mine little more than I did my bookstore once Amazon arrived.

I doubt the fate of financial services will be much impacted by my misgivings. I'm already voting for the outcome when I consider Citi's grocery loan, as are the millions of other consumers making similar choices every day. Embedded finance isn't just here to stay - it's here to win.

Cocktail Talk

Cornerstone released its annual bank survey with answers from 300+ participants. I find it particularly interesting that there's significant discussion of AI, crypto, and other emerging themes while over 40% of banks and credit unions seem to still be "exploring" cloud and APIs. That conversation started over 20 years ago and they still haven't gotten moving. No wonder tech companies are making inroads into banking. (Cornerstone)

I find it difficult to wrap my head around the scale of the three big cloud players: AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform. They're all bigger than Dow 30 member Salesforce (AWS is 3x bigger) and growing almost twice as fast. Their scale leads to some truly astonishingly large partnerships. Snowflake, a $61 billion company, co-sold more than half their 4Q21 deals with one of the big three cloud players. A full $700 million in revenue is tied to the big three. That and many more similarly deep insights in the full report. Thanks to Liberty for sharing. (Software Stack Investing)

"Geniuses of the past were aristocratically tutored." It appears there is more truth to the author's analysis than we might typically be comfortable expressing. Grade schooling today is focused on the average - how do we get everyone to do well enough and the ones lagging behind to catch up. Far less attention is given to how to allow the geniuses to excel. The author proposes something at once revolutionary and pedestrian - what if we rewound the clock and returned to individualized attention from truly skilled teachers to curate the interests and knowledge of today's youth? Thanks to Farnam Street for sharing. (The Intrinsic Perspective)

Giant cyborg cockroaches. Seriously. Scientists are using tech to control 3-inch Madagascar hissing cockroaches, ostensibly to help in search and rescue. (Freethink)

Your Weekly Cocktail

This cocktail shouldn't work, but it does.

The Devil's Soul

1.50oz High West Double Rye!

0.50oz Del Maguey Vida Mezcal

0.50oz Amaro Averna

0.25oz Aperol

0.25oz St. Germain

Pour everything into a mixing glass. Add ice until it comes up over the top of the liquid. Stir for 20 seconds (~50 stirs) until the outside of the glass is frosted. Strain into a rocks glass.

This cocktail simply makes no sense. Nothing about the combination of liqueurs is reminiscent of anything in my repertoire. The ingredient list looks like something a high schooler would make when they're stealing booze from their parents and dumping it into a water bottle - just a little bit of each so no one notices. And yet, what a cocktail. The spice of the rye with the smokiness of the mezcal. The floral notes of elderflower with the bitterness of Aperol. Averna doesn't usually play nice but here it blends beautifully. Maybe those high schoolers are onto something after all - it's a work of art. I'll be going back for seconds.

Cheers,

Jared