Fat Tailed Thoughts: Inflation & Vaccines

Hey friends -

Thanks to the many of you last week who shared the letter and wrote back, encouraging me to keep writing and providing helpful critiques. I’m very much appreciative. Keep it coming!

In this week's letter:

What is inflation?

How we went from 31M COVID-19 vaccines in all of 2020 to 413M in the first three months of 2021

Facts, figures, and links to keep you thinking over a drink

A drink to think it over

Total read time: 16 minutes, 21 seconds.

Prices go up

There's been lots in the news recently about inflation. Is it going up, will it go up too quickly, why hasn't it gone up more quickly for the past couple of years, and endless similar speculation. There's been painfully little discussion of what inflation actually is.

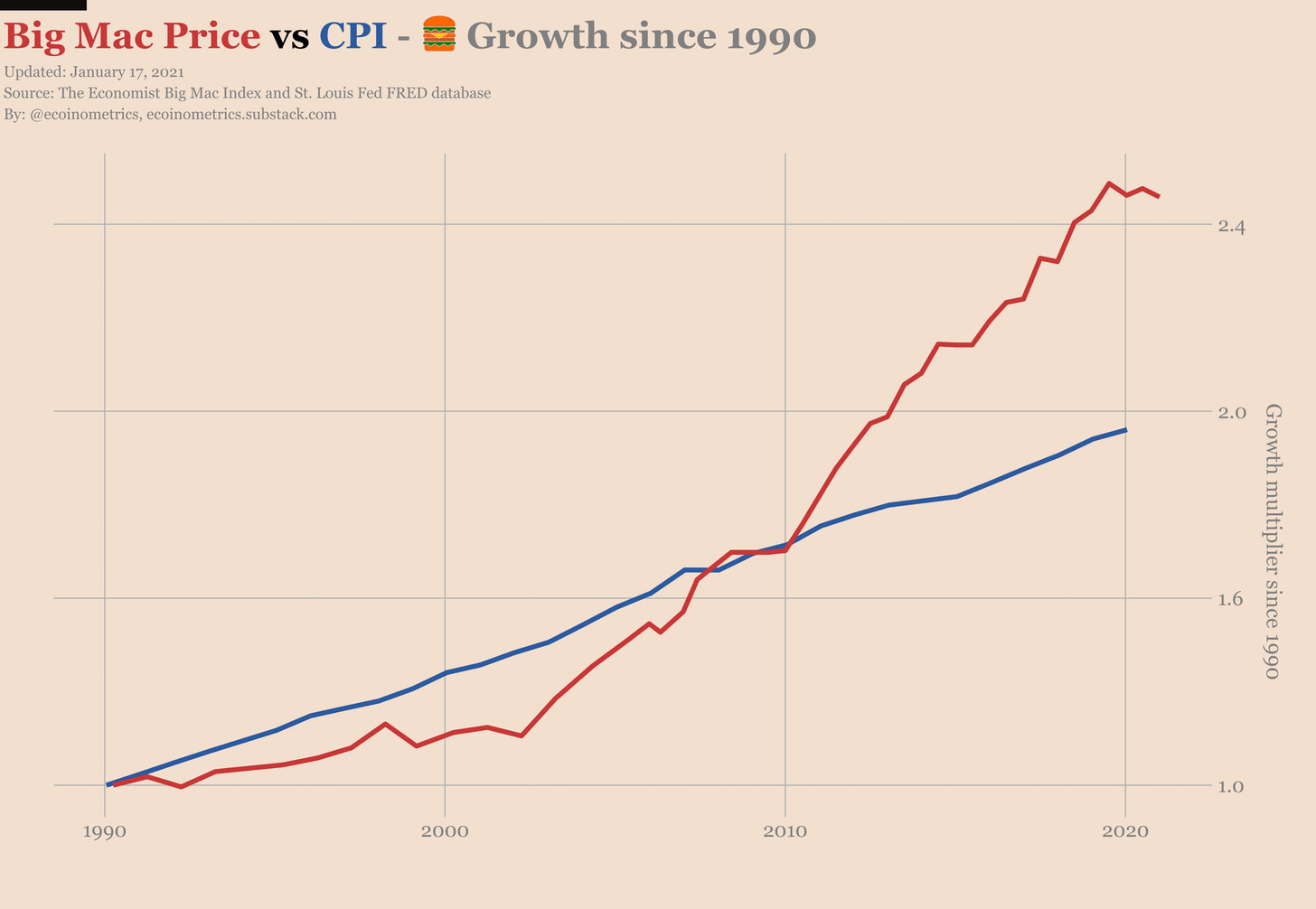

You may already have an intuitive sense of what inflation is, perhaps from an economics class or living through high inflation in the US during the 1970s. Consumer price inflation is what you probably have in mind - the same stuff costs more today than it did yesterday. This is the inflation your parents and grandparents complain about: "back in my day, coke cost a nickel." The Economist came up with a tasty way to measure this back in 1986 with the Big Mac Index. It's exactly what it sounds like - it tracks the price of a Big Mac over the years.

The price of a Big Mac in US dollars increased 2.5x in the past 30 years, implying average annual Big Mac inflation of 3.20% per year. The ingredients have mostly stayed stable over time (two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions, on a sesame-seed bun), as have McDonald's gross margins (revenue minus cost in the inputs). This means the increasing price of a Big Mac is reasonably representative of the changing prices of the ingredients, plus the changing shipping and processing costs, plus the changing labor costs. We can state that, on average, the price of all those goods and services increased about 3.20% per year. We could go even further and analyze the changing price of a Big Mac by country to understand country-specific Big Mac inflation.

All of this tasty analysis makes the Big Mac a useful starting place to think about inflation. If we take a bit of a more formal approach, we'll find there are generally three different "inflations" we could be thinking about: consumer price inflation, asset price inflation, and monetary inflation.

Headline inflation: consumer price inflation

Consumer price inflation is when the price of goods and services you and I buy increases over time. We can create indices to track that price change. A consumer price index is a specific basket of those goods and services. The Big Mac is an informal consumer price index. Each month, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes an official Consumer Price Index. When you see headlines about inflation, the media is usually reporting on a price change in the Consumer Price Index.

One would hope that two ways of tracking the changing prices of goods and services would roughly approximate one another. Not so. Whereas the price of a Big Mac has increased 2.5x in 30 years, the Consumer Price Index indicates prices have only increased 2x. That's a big difference. What's going on here?

It turns out to be difficult to create a "basket of goods and services" to measure over time. For the basket to be a useful measure of price changes over time, the stuff in the basket and the weightings among the stuff in the basket have to be relatively unchanging. More simply put - the basket should reflect what we actually spend money on and how much of our money we spend on each thing for every time period. If the goods and services mix changes over time, that's problematic. If how much money we spend on each good or service as a percent of total spending changes, that's also problematic. Healthcare is a prime example of both problems. The services we purchase have changed - think of all the end-of-life care that is now available to the elderly. And we spend more. A lot more. In fact, we spend 2.5x more than we did in 1970, as compared to everything else we spend money on.

Consumer price indices are difficult. There's no easy answer here. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes regular updates as they update their methodology. The best answer is that they're directionally correct, but we should expect any individual index to frequently be wrong in its magnitude.

Frothy valuations: asset price inflation

Asset price inflation refers to the increasing prices of stuff you could invest in. Stocks, bonds, gold, art, Bitcoin, real estate, you name it. To make the conversation easier, we'll call this stuff you can invest in "financial assets." The changing prices of financial assets tell a very different story than the changing consumer price index. If we look at the financial asset price changes from 2009-2019, it appears that prices increased much faster than the consumer price index.

But this is an incomplete story because increasing financial asset prices may be great for someone who already owns a lot of financial assets, but not for those that don't own a lot yet. We can compare income to financial asset prices and understand someone's ability to purchase more. If your income is increasing faster than the financial asset prices, the price of financial assets may be declining relative to your ability to purchase more.

We're going to replace financial asset prices with "net worth" for this analysis. Changes in your net worth are a good approximation of the changing prices of financial assets because most of your net worth is tied up in houses, stocks, bonds, and other financial assets.

Over the past 30 years, net worth has increased from 540% to 740% of income.

Let's take a look at two different families to understand what this means. For an average family who has had an annual income of $100K per year since 1990, they've seen their net worth increase from $540K to $740K. That's great! But what about a younger, up-and-coming family who had an annual income of $100K in 2020 and zero net worth? Financial assets are 200% more expensive!

Even this isn't the whole story because not everyone has the same income. Income growth has been much higher for higher income brackets than lower-income brackets for the past 30 years.

If you had Top Quintile income in 1990, you earned about 75K per year. If stayed "average" over the next 30 years, your income increased 330% to $250K per year by 2020. Your 330% income growth significantly outstripped the 200% increase in financial asset prices, so financial assets became relatively cheaper. But if your income was in the bottom quintile and you stayed average, you had a very different experience. Your income increased 100% from $7K to $15K, which was half the growth rate of financial asset prices. Even as your income grew, financial assets became more than twice as expensive.

Like with trying to get the exact right answer for consumer price inflation, there's no "right" answer for asset price inflation. The "true" financial asset inflation is dependent on the question you're asking. Compared to an individual's ability to purchase more financial assets, prices are higher for low-income individuals and lower for high-income individuals than they were 30 years ago.

Mo' money, mo’ problems: monetary inflation

Monetary inflation is perhaps the least intuitive of the three measures. Monetary inflation is exactly what it sounds like - more money in the system. We're going to avoid getting sidetracked with a "what is money" conversation for this week, but money is more than just the cash in your pocket. Our definition of money here includes cash and also includes checking accounts, savings accounts, Federal Reserve Deposits, and a couple other instruments.

More money generally leads to increased consumer prices. Think about a country where every person has $100 in their pocket and the only thing to buy are widgets. If I give you an extra $50, you might go out and spend it on an extra widget. It probably won't have a big effect on overall prices because your extra $50 makes only a small difference in the total amount of stuff bought. But if I gave everyone an extra $50 and everyone tried to buy extra widgets, we'd have a widget shortage. The widget sellers would increase the widget prices to compensate.

The correlation isn't perfect. Monetary inflation tends to be higher than the consumer price index over time because of productivity gains. When faced with a shortage, maybe one of those widget sellers invests in a factory so they can produce twice as many widgets at a lower price than the other sellers. The widget prices will likely still increase - the factory has to be paid for - but less than the increase of money in the system because sellers now produce widgets more efficiently. This story is what's been playing out in the US for the past 40 years (M2 Money Stock is the formal name for our money definition above).

In general, the goal of monetary policy is to supply the right amount of money into the system to keep consumer prices stable. In the US, stable means increasing at an average of 2% per year. Other countries can and do target different definitions of stable.

Will the real inflation please stand up

Where does all of this leave us? We have the Consumer Price Index indicating ~2.5% inflation since 1990, a Big Mac inflation indicating 3.2%, and financial asset prices that have been increasing even faster in absolute terms, but not always in relative terms depending on your income. We also have monetary inflation that is increasing faster than the Consumer Price Index, and one would think all of that additional money in the system has to go somewhere.

The answer is that the "real" inflation rate is dependent on your situation. If you're low income with little-to-no net worth, then the inflation rate is likely quite high. The prices for goods and services are increasing, the price to purchase financial assets is increasing even faster, and income is not increasing as quickly. If you're high-income with a large net worth, then the inflation rate is likely much lower as the changing prices for goods and services are less impactful, net worth is increasing quickly, and income is increasing even more quickly.

Not all is doom-and-gloom. Lower-income and lower net worth individuals often have debt. Most middle-income and middling net worth individuals similarly have debt, often in the form of a mortgage. Inflation gives leaves you with more money to pay down debt. If the debt is fixed-rate, as is the case with all federal student loans and many mortgages, then inflation can be a meaningful boom. Like the income perspective, this cuts both ways. If you're a retiree receiving a fixed number of dollars as a pension or similar, you have relatively less money to spend as inflation increases.

So what is the real inflation rate? Well, it depends on what you're trying to measure and from whose perspective. Digging a little bit deeper will likely be far more helpful than just the headline.

For those interested - while researching this, I stumbled across Lyn Alden's Ultimate Guide to Inflation. It's an hour read and exceptionally well written.

Covid vaccine production: from zero to billions

Just a few months ago, I was asked when I thought I'd be eligible to get vaccinated. My bet was September at the earliest, more likely October. I had seen the early numbers on vaccine production, heard the news on our test shortages, and assumed that at the current rate and pace it'd be many months yet before vaccinations were a reality.

I've rarely been so happy to be so wrong. We're going to look at why I was so miserably wrong and how vaccine production ramped up beyond my wildest expectations.

Exponential growth looks very linear

I failed to recognize the difference between exponential growth and linear growth. Over short time periods, exponential growth looks a lot like linear growth. Over long time periods, it's a different story.

It's helpful to keep in mind that the exponential/linear comparison isn't just true early on when something is just beginning to grow. It remains true in every short time period. As a result, it always remains difficult to figure how something is growing without diving deeper into the growth itself. Even once you've identified exponential growth, you can end up with ridiculous conclusions if you project continued exponent growth over long time periods.

There's almost always a helpful story to make the point and exponential growth is no exception. A craftsman creates a beautiful chessboard for his king. The king is wowed by the chessboard and asks the craftsman how he wishes to be paid. The craftsman, being both clever and smart, asks the king for grains of rice: one grain on the first square, two on the second, four on the third, and so on until all 64 squares are filled with rice. The king laughs at the meager request and readily agrees. Unfortunately for the king, he had a poor grasp of exponential growth. While the first couple squares are just a few grains of rice, by the time we get to the 64th square we have eighteen quintillion grains of wheat, roughly the weight of 237 billion African bush elephants. As a strong reminder of the power of exponential growth, keep in mind that the second half of the chessboard has 4 billion times more rice than the first half. Ridiculous indeed.

A long time ago in a pre-COVID-19 world...

We need to set the stage of vaccine production pre-COVID-19 to appreciate just how remarkable COVID-19 vaccine production is. In 2006, the World Health Organization launched a global action plan to ramp vaccine production. The goal was to develop enough production capacity to immunize 70% of the world's population with a two-dose vaccine within 6 months of a vaccine virus strain being available to vaccine manufacturers. The folks at the World Health Organization had remarkable foresight. The quote below is the open paragraph to the global action plan:

To mitigate the potential impact of an influenza pandemic, control interventions include two strategies – one, a non-pharmaceutical approach such as social distancing and infection control, and the other, a pharmaceutical approach such as the use of influenza vaccines and antivirals for treatment and prophylaxis. In an influenza pandemic, most of the world’s population will be highly susceptible to the virus infection and it is conceivable that the virus will spread rapidly. The availability of a pandemic vaccine will be delayed by several months because of the requirements for vaccine formulation and production lead-time. Furthermore, it is probable that insufficient production capacity will restrict global access to the vaccine, at least during the first phase of the pandemic.

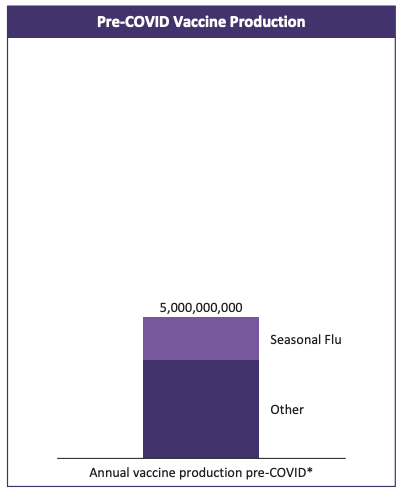

The plan dramatically increased vaccine production capacity but fell short of the 70% goal. By the end of 2015, seasonal vaccine production tripled to 1.47 billion seasonal vaccine doses annually and the potential capacity for pandemic flu vaccines quadrupled to 6 billion doses. That capacity was almost unchanged at the end of 2019. If we look at total vaccine production by all manufacturers for all vaccines, it totaled ~5 billion doses in 2018.

How many vaccines are required to get to the 70% vaccinated "herd immunity" to COVID-19? 10 billion two-dose vaccines. That's a 3x increase in production compared to 2019. How long does that take normally? Well, it took WHO 10 years to triple the production of flu vaccines.

Unbelievably, we're on track to produce almost the entire 10 billion COVID-19 doses in 2021. What I originally thought was linear growth turned out to be the beginnings of exponential growth.

10 Billion, that's a lot

How could we possibly increase capacity so quickly? Your instinct might be what hits the headlines - governments spending lots of money. While governments around the world invested meaningfully in advance of the pandemic and have provided direct funding for late-stage clinical trials, the capacity increase is in large part funded by the private sector. One of the most important roles the government played was to guarantee demand. Take Pfizer for instance. The headlines stated that they received $2B in funding, whereas the reality was that Pfizer received nothing until the drug was approved by the FDA and the first 100 million doses were delivered. Ramping up to 100 million doses is a huge undertaking, never mind that the US government also secured rights to the next 500 million Pfizer doses in the event Pfizer was successful. With government demand in place, the private sector went to work solving an enormous manufacturing and distribution challenge.

The private sector set up novel partnerships that allowed companies to specialize. A handful of companies invented novel COVID-19 vaccines. These are the companies you hear about in the headlines - Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and the like. But inventing the vaccine is just one-third of the challenge. The vaccine still has to be manufactured at scale and distributed around the world. Partnerships to the rescue.

Serum Institute of India is the largest vaccine manufacturer in the world. 2020 annual non-COVID-19 vaccine production exceeded 1.5 billion doses. They struck a partnership with AstraZeneca to manufacture AstraZeneca’s vaccine. Think about for a moment how unusual this is. AstraZeneca has its own manufacturing capabilities. This is a bit like Burger King allowing McDonald's to use their kitchen to produce Big Macs. How did such an unlikely partnership happen?

Second-source agreements played a critical role. A second-source agreement is when a first-source (AstraZeneca) allows a second-source (Serum Institute) to manufacture their product. The Gates Foundation, among others, stepped in to help offset the financial risk for the second-source companies. The second-source doesn't want to ramp up production capacity until the first-source has a successful vaccine. But if the second-source waits until everything's approved, then it will take much longer for the vaccine to make it to market. The Gates Foundation agreed to compensate the second-source if the first-source failed to get approvals. This allowed the second-source to start building production capacity much sooner.

The second-source agreements must have been a bit of a homecoming for Bill Gates. Microsoft's first big breakthrough came via similar arrangements 30 years ago with IBM in 1981. IBM contracted Microsoft for $430,000 to produce an operating system for the IBM Personal Computer. IBM went on to sell hundreds of thousands of PCs, all bundled with Microsoft operating system. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Are we out of the woods?

Production is on the right track. We'll continue to face new challenges with production as the many inputs to vaccine manufacturing also try to ramp up to the new scale. The good news is that these suppliers have guaranteed revenue if they can move fast enough. This is the government's guaranteed demand working at scale, trickling all the way down through the supply chain.

Distribution remains challenging. The US looks to be on a healthy track for distribution, but we're struggling with waning demand. The challenge globally is that most of the distribution has been gobbled up by the rich countries. Important organizations including GAVI are working tirelessly to ensure vaccine distribution and access globally but there's much more work to do. The Economist publishes regularly updated predictions on when each country will reach the 70% vaccinated herd immunity. Much of the world is predicted to be 70%+ vaccinated by mid-2022, but Africa remains an outlier. With 1.2 billion people on the continent, distribution to Africa will continue to be both important and difficult.

I remain both hopeful and optimistic. The retooling of existing vaccine manufacturers and extraordinary increase in production capacity happened on a timeframe and scale unseen since World War II. Even more remarkably, the private sector has played a leading role. With such incredible results in so short a time period, I'm confident we'll solve distribution as well.

Cocktail Talk

Inflation forecasts are mostly useless. Simply predicting it would be 2% in the upcoming year was more accurate than the financial market predictions. The major forecasting methods were all off by 1.5% or more. Keep that in mind next time you see a pundit on TV predicting inflation rates.

Continued debates in Congress on how we spend our tax dollars. A poll of US citizens estimated that we spend 26% of the federal budget on foreign aid. It's actually less than 1%, but that still adds up to $35B annually since 2000. That's the most of any country. For context on how the US prioritize's spending: Medicare is 20x more at ~$750B annually and is projected to grow at over 7% per year.

The Biden administration recently suspended oil and gas leases in the Alaskan Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. This follows on one of the first executive orders for a likely reversal of the 2020 act permitting timber harvesting in the Alaskan Tongass National Forest, the US's largest national forest. The US is currently home to 8% of the world's forests, ~1/3rd of the total land in the US. Those numbers indicate that the US is batting above our weight class as the country only covers 6.1% of the world's total landmass.

And in unrelated but very cool news, graphic designer Martin Vargic released an updated and expanded map of the internet. The landmasses represent the major web properties by traffic, all spiraling out from the major internet providers in TCP/IP Straights. High-resolution version here.

Your Weekly Cocktail

Tiki drink season’s here! We’re kicking it off with a classic.

Hurricane

1.5oz Plantation 3 Stars (Light Rum)

0.5oz Smith & Cross Jamaica Rum (Overproof Dark Rum)

0.5oz Passionfruit Liqueur

1.5oz Lemon Juice

Pour everything into a blender. Fill with ~8oz of ice. Blend until smooth (add more ice if needed to get the consistency to that oh-so-perfect slushy). Pour into a hurricane glass and top with something that’ll make you smile.

I wandered away from the original that’s served at Pat O’Brien’s in New Orleans. Pat O’Brien’s Hurricane calls for orange juice, grenadine, to be poured over ice, and uses passion fruit syrup rather than liqueur. It was over 90 degrees out and I wanted a slushy that was a bit less sweet with a bit more bite. So that’s exactly what I made. Enjoy!

Cheers,

Jared