Fat Tailed Thoughts: Bundling & Unbundling

Hey friends -

In this week's letter:

Bundling and unbundling: how the internet continues to change the way we purchase

Facts, figures, and links to keep you thinking over a drink

A drink to think it over

This week's note breaks the two-topic pattern with a longer, single-topic letter. Please let me know what you think!

Total read time: 17 minutes, 54 seconds.

Would you like fries with that?

Bundling is one of the great business innovations. Slightly different than the bundling popular in colonial America, bundling today is the combining of multiple products or services into a single package to be purchased by the consumer. Perhaps the most familiar of all bundles is the happy meal - a burger, fries, a coke, and a toy for less than it would cost to purchase each individually.

We're going to take a quick look at what bundling is, then layer in how the internet has supercharged bundles. With our new internet-bundle toolkit, we’ll explore the rapid pace at which music and movies are going through bundling and unbundling before turning attention to the craziness going on in collectibles and explore what bundling might look like there.

Bundle up!

What follows here is shallow dive into bundling, just enough to get us firmly grounded in the concept. Much of this is borrowed from Shishir Mehrotra's longer and brilliant piece, which you can also learn about on his podcast discussion with Patrick O'Shaughnessy on Invest Like the Best.

What helps make the bundle so powerful is that three different consumers all look at the same bundle and come to different conclusions. Returning to our happy meal:

Someone on a budget thinks: “This is great - I pay for a burger and fries and get a free coke!”

Someone out with a friend thinks: “This is great - I pay for a burger and coke and we get free fries to split!”

Someone with a young child thinks: “This is great - I get a meal and my kid gets a free toy!”

Bundles work because bundle purchasers, the consumers, get more value at a lower price than if they bought each service on its own. We’ll formally define our bundle as something a consumer purchases that includes access to multiple goods generally (though not always) from multiple providers.

Here we have to break out our consumers into two buckets - super-fans and casual-fans. For a given product, super-fans will search out the product and purchase it at the à la carte price, where the la carte price is what they pay to purchase that product standalone and not in a bundle. Casual-fans won't search out and purchase the product, either because they don't want to search or because they don't want to pay the à la carte price. The bundle provides benefits for both the super-fans and casual-fans - super-fans get their "super-fan" product in addition to many other products for which they're probably only casual-fans, and casual-fans get reduced search costs and a lower average per-product price.

For the bundle to be seen as a good deal by the consumer, the bundle price has to be less than the sum total of the à la carte prices and the consumer needs to be able to calculate the savings. That means that the consumer needs to be able to purchase each item à la carte so they can make the decision to “save money” by purchasing the bundle. If you’ve ever had a friend complain about paying for the whole cable package just so they can watch XYZ channel for their sportsball team, you’ve experienced the disconnect that happens when it’s not clear how much additional value they’re getting from the bundle.

We can create even more value for the consumer by bundling in products that can only exist as part of the bundle, such as the Netflix browsing and recommendation engine. Netflix can only make it easier to find new movies if you purchase the entire "Netflix bundle," a good example of reducing search costs for consumers.

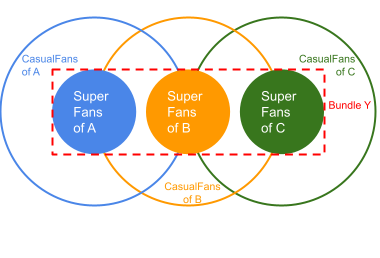

We still need to figure out how to put together the revenue-maximizing bundle. If we dive into a bit of math, we'll find revenue-maximizing bundles minimize super-fan overlap and maximize casual-fan overlap. This is probably a terribly counterintuitive answer because our instinct as consumers is that we like bundles that include lots of stuff we really like. If we reverse the problem and look at it from the bundler's point of view instead, "minimize super-fan overlap" starts to make more sense.

Let’s imagine four products - hamburgers, coke, fries, and curly fries. If we’re currently selling a hamburger and fries bundle, we’re probably not going to attract many new consumers by including curly fries - most of the curly fry super-fans are also fries super-fans, so they’re already purchasing the bundle. We’ll also be constrained on the incremental price we can charge for our hamburger + fries + curly fries bundle because consumers likely won’t pay up that much to include curly fries if they’re already getting regular fries.

If instead, we add coke to the mix so our bundle is a hamburger, fries, and a coke, we’ll likely get many more new consumers because the super-fan overlap between coke and fries is much smaller. We’ll also get the casual-fans for whom the addition of a coke adds enough incremental value that the whole bundle is now attractive. You can see this below visually; the example works just as well with whatever you want to swap in for A, B, and C.

Even though it's counterintuitive, the bundler sells more bundles by including a diverse product set rather than products with significant super-fan overlap.

To summarize our bundle - we're selling a basket of products or services:

at a single price that’s less than the cost of purchasing each product or service individually,

where the consumers can purchase each component product or service at an à la carte price if they so choose, and

where the included products and services minimize super-fan overlap and maximize casual-fan overlap.

I think we have enough of a handle on bundling, but we need to layer in how the internet has supercharged bundles to get insight into the craziness that follows.

There's only two ways of making money: bundling and unbundling

In 1995, Jim Barksdale was famously quoted, "Gentlemen, there’s only two ways I know of to make money: bundling and unbundling," while on the roadshow with Marc Andreesen to take Netscape public. That's turned out to be an incredibly powerful idea in the internet era.

The internet brings together three core concepts that have massive implications for bundles:

Zero cost of distribution,

Minimized integration costs, and

The 1000 true fans.

Zero cost of distribution is the insight that anyone can distribute a product, service, idea, or bundle online to billions of people on the internet for effectively zero cost. Think about your access to news as one example - The New York Times used to deliver news through massive printing factories and an army of mail trucks, and now they can deliver you news to your email.

Minimized integration costs is the concept that entire businesses can exist only online and just create the "lego blocks" needed to build a bigger business. Even if you don’t always realize it, you interact with many of these “lego blocks” every day including email marketing (MailChimp), text messaging (Twilio), payments (Stripe), and help desks (Zendesk). These companies sell to other businesses who, in turn, use the services to make emails and text messaging and the like available to you and me. To sell more to other businesses, these lego block companies increasingly make it easier and cheaper to use their services. Taking one example from above, Stripe made it easy for customers to enter their credit card and pay - and now almost 2 million businesses decided it's easier to use Stripe's payment “lego block” than create their own payments service. That’s over 18% of online stores and growing. Stripe is minimizing integrations costs even further with their recently announced Payment Links which allows anyone to accept online payments without even setting up a website.

The 1000 true fans is the idea that a creator doesn't need millions of fans or followers to make a living. They only need 1000 "true fans" who will buy anything they produce. If you put on enough concerts or write enough blog content to get 1000 people to spend $100 a year with you, you're making $100,000 per year. This means we can create novel bundles and almost inevitably find a big enough group of consumers that the bundle generates meaningful revenue.

Our three internet concepts have made bundles way more powerful, and made and unmade entire industries at a rate not seen before:

Zero cost of distribution means we can get our bundle in front of lots of potential consumers for almost nothing;

Minimized integration costs means that we can include more and more products in our bundle at a minimal additional cost; and

1000 true fans means that we’ll almost always find a super-fan group for the new product in the bundle.

Alright! Enough with theory and onto reality. Let’s see how this bundling stuff has played out in music and video.

Internet killed the radio star

Let's first take a look at bundling in the music industry starting with the once-prominent CD industry. In 1998, the band Barenaked Ladies releases the album Stunt and the album reaches number 3 on the Billboard 200. Like many similar albums, it contains one hit single ("One Week") and twelve other songs. Expressed differently, in 1998 your bundle choices were the CD and the radio. The CD included one super-fan product (the hit song), a bunch of casual fan products (the other songs), and no ability to purchase the songs à la carte. Radio came with massive search costs as you waited for the song to hopefully come on air. I, like many other consumers, bought the album for the one song and was annoyed to spend money on songs I didn’t want while the industry was fat and happy.

I wasn't the only one dissatisfied with the bundle choices. In 1999, Parker and Fanning launched Napster with the insight that you could unbundle the album and allow us to share individual songs. Now anyone with an internet connection can share songs with everyone else at practically zero cost of distribution. This spelled disaster for the US music industry whose revenues peaked at $22.7B the same year (using 2020 adjusted dollars). Fast forward to 2003 when iTunes is finally released for Windows and now anyone anywhere can purchase almost any song for $0.99. Think about what that means - Apple created a brand new bundle by rebundling individual songs into the iTunes/iPod bundle.

But what about us casual-fans who like many songs but not enough to pay even the $0.99 to purchase? We’re still stuck with the radio. A Swedish startup named Spotify changes the game in 2006 and launches with the idea that you can pay a flat monthly fee to listen to any of the songs on the entire platform. The startup is powered by some of our “lego block” companies from earlier - Stripe for payments and Google Cloud to host all of the songs - which allows them to compete on a global scale and attract over 356 million active listeners. This is a whole other type of rebundling, combining a subscription fee with unlimited songs!

The effect on the industry has been dramatic. Pre-internet, album sales were the only realistic way to get music to consumers. The high cost of distribution through record labels, CD manufacturers, and retail stores meant that you and I were limited to just 5000 new albums in 2000. The internet means everyone can distribute their music for free, and the Spotify bundle allows over 1.2 million artists to have audiences of over 1000 active monthly listeners. After years of revenue declines, all these new bundles are starting to generate real revenue with 2020 US music industry revenues reaching $12.2B and growing at almost 11% per year. These internet-enabled bundles are creating new value for us consumers, and we're voting for them with our pocketbooks.

Remember Blockbuster?

While the music world feels like it's starting to normalize around new bundles for the time being with new emerging battlegrounds around podcasts and content licensing, the television and movies world is very much in the thick of change. We're going to focus on movies.

Let's rapidly walk through the first couple (un)bundlings to bring us up to the internet era. The first dedicated movie theaters launch in the early 1900s and are the only practical way to view films for the next 40+ years. TVs launch commercially in the US in 1938 and cable television occasionally features movies, leading to our first bundle made up of cable + occasional movies. A la carte movie purchases at theaters is still the primary method of watching.

VHS and Betamax duke it out in the 1970s and 1980s, with VHS as the eventual winner. Blockbuster launches in 1985 but fails to offer a true bundle by charging both for the membership and an additional per rental charge (and late fees). There’s a novelty in that you could watch movies in your home and not just what the cable company or theater was showing, but Blockbuster left the door open to get beat by a proper bundle. Netflix creates that bundle in 1999 with a subscription + unlimited rental-by-mail offering. We also have a couple other à la carte models (e.g. video-on-demand) and variations on our cable + occasional movies bundle (cable expands into dedicated move channels) that appear in the '90s.

It takes almost another decade for the internet to mature to support streaming video at scale. In 2007, Netflix launches a new type of bundle, subscription + unlimited streaming, and throws the entire industry into hyper-competition. Streaming means you can watch any movie, anytime, anywhere with just an internet connection, which massively outcompetes the subscription + single rental offering from Blockbuster. The company quickly fades from relevancy with revenues peaking at $6 billion in 2004 and the company going bankrupt by 2010.

Streaming didn’t just kill off Blockbuster, it also massively bloodied the original cable video + occasional movies bundle. Cable video subscriptions have declined every year since 2012 and the number of Netflix subscribers surpassed the number of cable subscribers in 2017. These subscriber numbers don’t even include Hulu, Vudu, and other competing streaming providers.

Netflix (and Hulu, and Disney+, and Peacock, and Apple TV, and HBO Max, and...) and chill?

We’re now well underway with a new hyper-competition battleground as content owners pull their content from existing bundlers like Netflix and rebundle their content into proprietary-content subscription streaming services like Disney+. This is a whole new type of subscription + streaming bundle built around single-company content. These content owners are betting that they have enough diverse super-fan content that they can create attractive bundles and don’t need to pay Netflix for distribution.

Netflix anticipated the value of proprietary content as early as 2013 with the launch of their first original content, House of Cards. Disney, HBO, and others came late to the game but have been moving rapidly in recent years. Case-in-point, Disney has taken advantage of zero cost of distribution and a wide-ranging content portfolio to scale Disney+ from 0 subscribers to over 100 million in just 18 months.

Remember how we emphasized that the revenue-maximizing bundles minimize super-fan overlap? The content owners aren’t just producing content anymore, they’re also bulking up through acquisitions to get even more diverse content to include in their bundles. Disney was the first mover and remains the largest, starting with the $4B Marvel acquisition in 2009, and subsequently purchasing Hulu (part 1 in 2009, part 2 in 2019), Lucasfilm (2013), and Fox (2019) for a combined $90B. Amazon’s not sitting still and recently announced they are acquiring MGM Studios for $8.5B.

To make the competitor bundles like Netflix less attractive, content owners including Disney are pulling content from other streaming platforms so it’s only available as part of their new content owner bundles. Note that they are not pulling their content from à la carte purchases. You can still go onto Amazon or into Best Buy to purchase individual movies. These à la carte options continue to provide critical value as price transparency to the consumer.

To the future and beyond!

While cable continues to crumble and content owners continue to rebundle content into new proprietary content bundles, we can look ahead to the two highly probable battlegrounds for the next round of hyper-competition: theaters and streaming-content aggregator bundles. We're just starting to see content owners bypass theaters to distribute new movies directly on their streaming platforms, a trend accelerated by the COVID-19 shutdown, and the pricing model diversity reflects the lack of bundle maturity. Wonder Woman 1984 was released direct to HBO Max and over half of all HBO Max subscribers watched the film on its premiere day. Disney is trying multiple models with their streaming service, releasing Soul for free and charging $30 for Mulan. While a new streaming-content aggregator bundle has yet to emerge, Roku is among those starting to nip at the idea with free trial bundles among smaller content owners. If the first two bundling battles are anything to go by, these next battles will come hard and fast.

We’re seeing similar dynamics play out in other industries that can offer internet-enabled digital content bundles. Microsoft Xbox and Sony Playstation are both exploring streaming video game bundles where you purchase a monthly subscription for a bundle of games (a quick note that video games are a $180B industry, bigger than movies and North American sports combined). Amazon offers an unlimited book bundle through Kindle Unlimited. The list goes on.

So what should expect to happen when something physical all of a sudden becomes digital?

Beanie Babies in the internet era

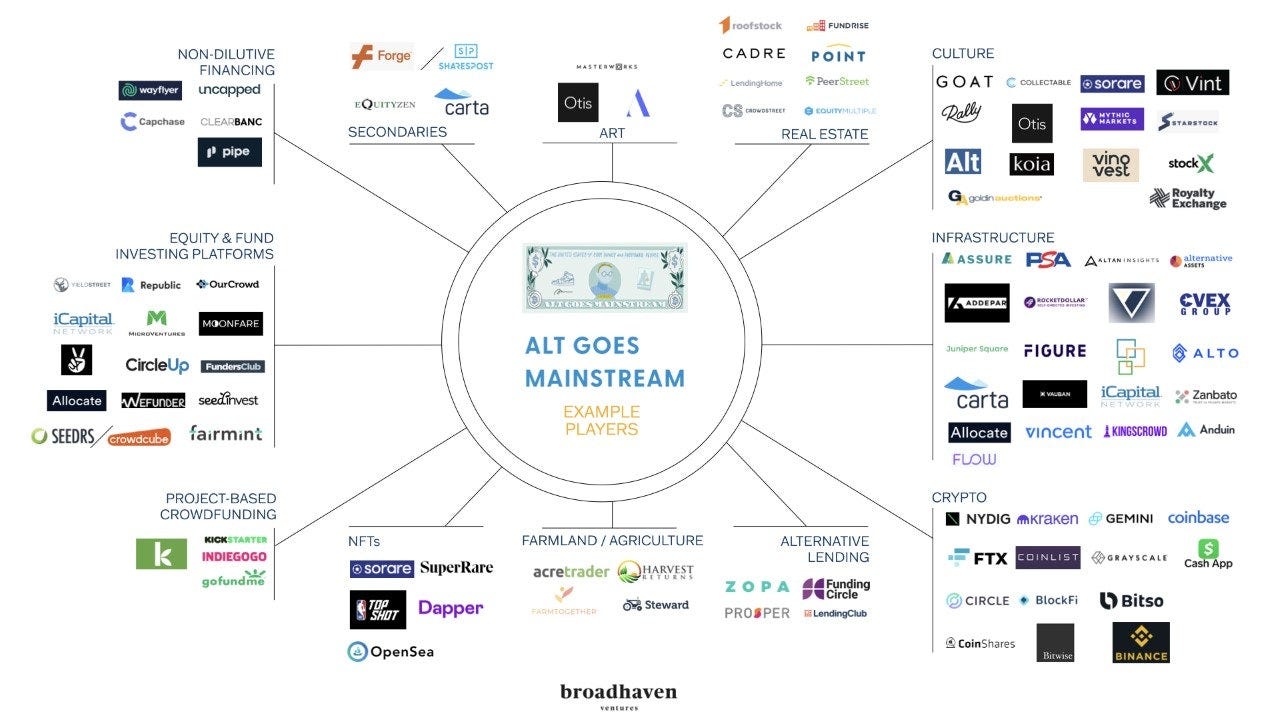

Collectibles are being digitized as we speak, but perhaps not the way you might expect. Startups are creating investment vehicles that purchase and own high-value collectibles where each “vehicle” is its own mini-company that owns just one collectible. The startup keeps the asset safe (e.g. in a physical vault) and sells shares of the mini-company to you and me. To take examples from the industry: with Rally you can own shares of a company that owns a 1955 Porsche 356 Speeder, and with Otis you can own shares of Magic Johnson's 1987 NBA finals sneakers. This transformation from “physical asset” to “shares” means that we’ve in effect digitized the asset. We can buy and sell the shares online and through apps without ever touching the physical good.

Coins, baseball cards, and comic books are all going through a similar investment company —> purchase collectibles —> sell shares transformation. Extending our bundling framework from earlier, we can think of each of these collectibles as an à la carte offering with all of the disadvantages that are typical of à la carte. The first major disadvantages are the costs incurred to become a collector - you have to find the app selling the collectibles, then download the app and create your millionth login for yet another service, and then participate in auctions to purchase shares of the collectibles. If you purchase shares of collectibles on different apps, you then have even more costs trying to keep track of your holdings across the multiple apps and logins.

We should expect this to change given what we’ve seen play out in music and videos. We can imagine a collectibles bundle that has shares of many different collectibles, priced at a discount to the per-share price of each individual collectible. Similar to the new movie bundles from the content owners, perhaps we offer a super-fan bundle that has shares of many baseball cards or many comic books. We can bundle the super-fan bundles to create super-bundles that have lots of different collectibles.

We already have a close analogy to these bundles in the stock market - replace "collectibles" with "stocks" and replace "bundle" with "index fund." You can invest in an index fund that bundles the 500 largest public companies like the S&P 500, or a tech-heavy index fund like the Nasdaq-100 which bundles the 100 largest non-financial companies of the Nasdaq Composite. These indices - really just bundles of public company shares - emerged as it became easier to buy and sell shares, and investment companies recognized that an index allowed investors to invest in many companies without having to own individual shares of each one. As it becomes easier to buy and sell shares in collectibles, new investment companies will create new collectibles indices that provide similar benefits to collectors.

It's worth noting that natively digital collectibles are also booming. Natively digital means there is no physical counterpart, such as an outfit for your character in a video game. Non Fungible Tokens ("NFTs"), which have been all over the news in recent weeks, are a new technology for digital collectibles. (Don’t worry if you’re not familiar with NFTs, we’re just going surface deep for this week). You can purchase digital art for $69M, a video clip of Lebron James dunking for $208K, or a CryptoKittie for $12.72. From our dive into blockchain in a previous letter and our look at bundling here, we shouldn’t be surprised to find that the growth of this new type of collectibles has already led to the launch of a new bundle, the first NFT indices.

Key an eye on the collectibles space. It's going through rapid and transformative growth which will inevitably lead to boom-and-bust in the short term and likely significant change in the long term. With all of the benefits of internet-enabled bundles, I'd be surprised if we don't see more collectibles bundles begin to emerge in the next few years as the industry matures.

Cocktail Talk

The unbundling of music has not been kind to CD sales. Vinyl on the other hand has seen a real resurgence with sales growing every year since 2005 and outselling CDs by 25% in 2020. Thank you hipsters.

The march to legalize drugs marches onward with the California Senate passing Senate Bill 519 to legalize possession of psychedelics. The bill is on its way to the House from where it could proceed to the desk of the California governor.

My apologies to the Cheez-It for missing the 100 birthday celebrations. If you were one in the know who had this on their calendar and remembered to order your Cheez-Itennial Cake, please do let us know how it was.

Exciting news for conservationists and Looney Toons fans alike out of Australia - Tasmanian Devils were born in the wild of Australia's mainland for the first time in 3,000 years. No news yet on their appetites.

Your Weekly Cocktail

Don’t know what to do with those over-ripe bananas? Already ate too much banana bread? I’ve got the cocktail for you!

Crucian Banana Squash

1 banananana

2oz white rum

0.5oz lime juice

Chop up the banana. Put the banana in a shallow container with the rum and refrigerate for ~4 hours. Pour the rum banana mix into a blender. Pour in the lime juice and ~4oz of ice (adjust as you go for slushy consistency). Blend until smooth. Pour into a glass or your mouth, we don’t judge here.

This is really a riff on the classic daiquiri (white rum, lime, sugar), using super-sweet bananas as the sweetener. When I first made this I figured it would be meh but a better use of overripe bananas than the trash. Whoa was I off the mark - this drink is awesome! The rum mellows the sweetness of the bananas and the lime cuts through the whole thing to give you that deeply sour back-of-the-mouth sensation. Blended, the bananas turn to mush which means I’m pretty sure this thing counts as a smoothie. And really, who doesn’t want an adult smoothie to end the day? Fair warning - watch out for the brain freeze.

Cheers,

Jared