Fat Tailed Thoughts: Credit Card Payments

Hey friends -

Welcome to our 10th letter! Thank you for the continued conversation, feedback, and encouragement - you're helping me become a better writer and providing the motivation to keep the letters coming. This week continues our foray into the seemingly endless corners of financial services.

In this week's letter:

Credit card payments: the many ways to pay, what happens after you swipe your credit card, why payments have been growing so quickly, and what's on the horizon

Facts, figures, and links to keep you thinking over a drink

A drink to think it over

Total read time: 14 minutes, 8 seconds.

From Credit to Checks to Cards

When we think of everyday consumer payments today, we mostly think of cash or cards. While settling payments with currency dates back millennia, paying with a debit or credit card is a relatively modern phenomenon. Card payments have been a remarkable growth story that continues today.

To start, we're going to take a whirlwind tour of card payments history before we go deep into how card payments in the US work today. From there we'll explore what's happening on the global scene where tremendous innovation hints at what's just over the horizon in the US. That'll give us a foundation to explore where we might be heading.

A brief history of not paying

For me, credit cards are magic. For most of us when we want something, we swipe a card and - magic! - the thing we wanted is ours. I'm pretty sure it's that "whoa! free!" feeling when you pay that's helped drive significant adoption. As it turns out, credit cards are far from the first invention to achieve such a feeling.

The history of credit - buy-now, pay-later - is a story almost as old as written history. It formally dates at least as early as Hammurabi's Code almost 4,000 years ago where interest rates were set in stone. "If a merchant lends grain at interest, for one gur he shall receive on hundred sila as interest [33 percent]; if he lends money at interest, for one shekel of silver he shall receive one-fifth of a shekel as interest."

As a species, we've been quite innovative in how we record such credits. Venice in the 13th century saw prolific use of bills of exchange - a promise to pay in the future - to facilitate global trade without needing to carry around gold. Checks showed up as early as the 1600s which entitled the recipient to funds stored by the payer at a bank. The Royal Bank of Scotland incorporated credit into that model in 1727 and allowed bank customers to "overdraft" their accounts.

Checks proved an attractive form of payment, so attractive that banks struggled to process all of the checks they received. The banks started meeting daily in 1770 to exchange checks drawn on accounts at each other's bank, a process known as clearing.

Jump forward another 100 years and Western Union debuted the first electronic money transfer, laying the foundation for a more rapid form of settling obligations. The next 75 years saw a variety of cards launched by individual businesses that allowed patrons to buy now and pay en-masse in a single bill at the end of the month.

In 1946, John C. Biggins of Flatbush National Bank of Brooklyn took this a step further and issued Charg-It cards to accountholders. Now any business within a two-block radius of the bank could accept a single card and know that the bank would process the sales receipts. Diners Club expanded on the model in 1950 by launching as a fully independent card company and grew to over 40,000 cardholders by the end of its first year. Just like with the check, credit was soon incorporated into this novel payment method in 1952 with the Franklin National Bank-issued credit card.

1958 became a pivotal year with the launch of both the American Express charge card and precursor to Visa, the Bank of America credit card. Whereas the former continued in the tradition of Diners Club charge card, the latter dramatically expanded on the credit model with over 60,000 BankAmericards mailed to residents of Fresno California to kickstart the first large-scale credit card business.

Consumers loved the credit card and Bank of America, then still California-centric, grew the business nationally by licensing the card system to other banks. This licensing model evolved into a consortium owned by the member banks and launched as an independent company in 1970. Together with international licensing operations still under Bank of America control, the consortium reorganized and rebranded as Visa in 1976.

Not to leave the other major card networks out of the discussion - Interbank launched as an interbank credit card association in 1966 as a challenge BankAmericard. After a series of expansions, acquisitions, and rebrandings, the association was rebranded MasterCard in 1979. Discover shows up in 1985 as the Sears issued credit card before, after multiple interim owners, it becomes an independent card company in 2007.

Except for a few latecomers, by the end of the 1970s, we have most of what we recognize as the modern card business. Visa is the dominant credit card company and American Express is the dominant charge card company. Both allow consumers like you and me to use plastic cards to purchase goods now that we pay for later. Both facilitate all of this electronically and increasingly digitally.

Despite the similarities at the surface, it turns out that there are meaningful differences in how they work once we go a bit deeper. It's here that the differing business models get interesting.

Scheming for Payments

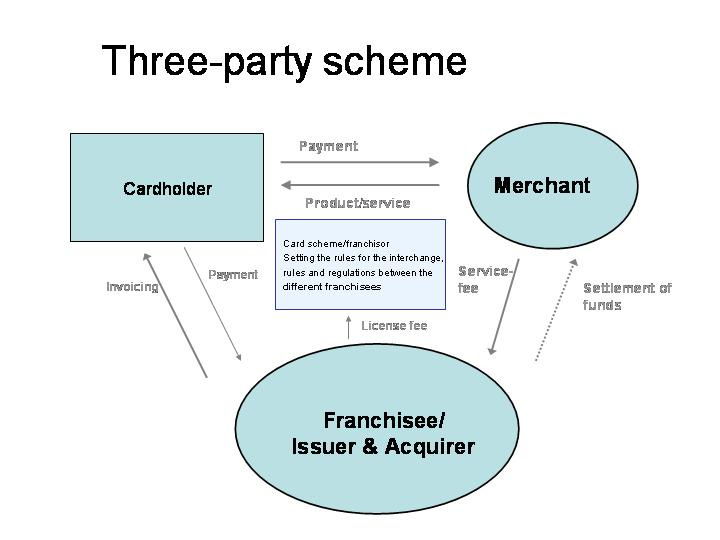

From the history of cards, we can see that each of the major credit card brands is its own payment network. We formally call these networks card schemes and they're typically operated by payment networks, also known as card associations. There are two main types of card schemes - three-party and four-party. American Express operates a three-party scheme whereas Visa operates a four-party scheme. We'll start with the three-party scheme.

Three-Party Scheme: Closed Systems

In a three-party scheme, there are (surprise, surprise) just three parties: the purchaser, the merchant, and the issuer/acquirer. As an issuer, American Express issues you a card. As an acquirer, American Express acquires new merchants to add to the network. Since it is both the issuer and acquirer, American Express also operates a payment network that connects everyone.

This three-party scheme means that a single company has complete control over the network. They decide who can be cardholders and who can accept cards. The model is a double-edged sword - the company can curate a better set of cardholders but they also take on cardholder default liability. It follows that American Express has historically only been a charge card meaning that cardholders had to pay the bill in full each month rather than defer payment and only pay interest. A charge card model limits the exposure that American Express has purchasers defaulting, although the company did start to offer a credit-based Pay Over Time feature in 2020.

Without offering credit so they can charge interest on payments, how does American Express make money? Mostly fees. Cardholders typically pay a fee to obtain a card and merchants pay fees every time the card is used. The business model is again a double-edged sword. Historically, fewer merchants accepted American Express because the fees were 1.5-2x bigger than Visa's, but some nonetheless found it worthwhile to accept in order to do business with the "curated" American Express cardholders who spend an average of 1.7x more per transaction versus other cardholders.

With such an attractive business where they can charge 2x their competitors, why would American Express start offering a credit model after over 60 years of success? They're seeing their fees per transaction decline. Let's quickly take a look at the four-party scheme to understand why.

Four-Party Scheme: Open Systems

The four parties in a four-party scheme are the same, but we split the issuer and acquirer into separate companies. The issuer is a bank that issues cards. The acquirer is a bank that services the merchant. Since the two are often different banks, we need a fifth party to facilitate a network that connects the banks. This facilitator role is where Visa fits.

In this four-party scheme, any bank can join as long as it meets the scheme's standards as defined by the payment network like Visa or Mastercard. Each issuer and each acquirer can choose to charge fees to their cardholders and merchants respectively, while Visa charges an interchange fee to the merchant for accessing the payment network.

Open vs Closed

Until recently, Visa's open payment network counted many more merchants as members than American Express's closed one. If you've ever seen a sign saying "no AmEx" at a store or tried to use an American Express card in Europe, you're likely familiar with the situation. As we've discussed in previous letters with the internet and with crypto, open systems tend to grow faster than closed in the long run. Cards associations are no exception.

In the last few years, American Express almost entirely closed the gap domestically and is making headway internationally. Clearly they changed something to compete. American Express has slowly-but-surely been opening its payment network to third-party intermediaries to onboard more merchants to the network. This newfound openness comes with a tradeoff - lower fees for American Express per transaction. Adding consumer credit to their business model is in part an attempt to offset the lower fees with new interest revenue from consumers.

This growth at the expense of lower average fees leads us to take a look at one of the most dynamic arenas of payments today - third-party processors and payment gateways. You might not be familiar with formal roles, but you will probably recognize the companies shaking up the space - Stripe and Square.

Processors & Gateways

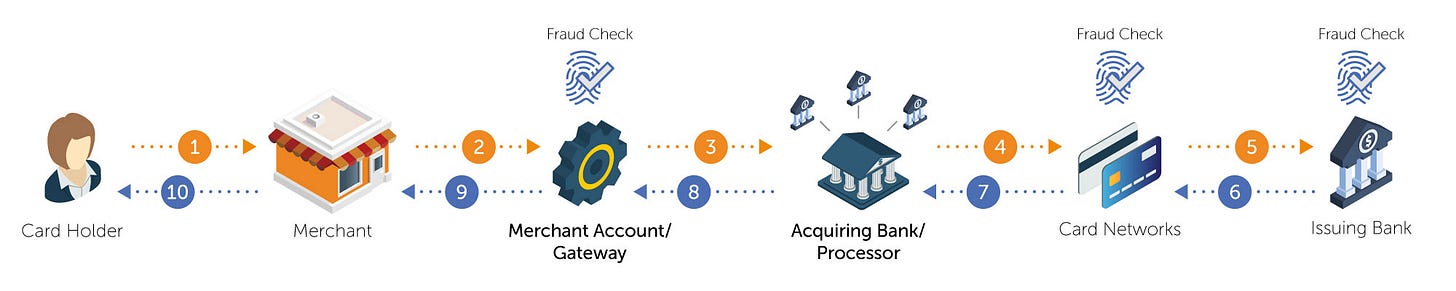

Our model of card payments is about to get a bit more complicated. To help the merchants accept payments, we can insert payment gateways. We can also insert a payments specialist - a third-party processor - to help the merchants process the payments and the banks acquire merchants.

Let's look at this entire process end-to-end to understand what's going on.

You're at a store online or in person, it doesn't matter for the moment. You provide your credit card information to the merchant, either by entering the information into a form or by inserting your card into a device. The form processor and device provider are the payment gateways, they connect your card to the payment network. From the gateway, your card information is securely transmitted to the payment processor who in turn passes it on to the card association. The card network identifies the bank that issued your card and passes along the information.

Everything now runs in reverse. The issuer bank authorizes the payment, sends that authorization back to the network, who reroutes to the payment processor, who routes to the gateway, and you see a message on the screen that says payment accepted.

We're not quite done yet. You might think you've paid but if you check your credit card account you'll see a "Pending" status next to the transaction because the merchant hasn't actually received the money. Merchants typically submit a single batch of authorized payments each day in a series of steps that runs the gauntlet one more time. Once the merchant submits the authorized payments to the payment processor, they're transmitted to the card association which communicates the amounts owed and payment destination to the issuer bank. The issuer bank then transfers funds to the payment destination. If the merchant is working directly with the acquirer bank, then the destination is the merchant's account at the acquirer bank. If the merchant is working with a third-party processor, then the destination is the processor's account at the acquirer bank and the payment makes one more hop from processor to merchant.

Whew. That's a lot of steps and a lot of parties involved just for a credit card payment. Just for fun, let's add in Apple Pay for yet another layer of complexity.

When you use Apple Pay, your credit card information isn't actually sent across the network. Instead, an encrypted token is sent from your iPhone through all of those parties and eventually to the payment network. The payment network, like VisaNet, recognizes that it is a token and sends it to a Token Service Provider. The token service provider decrypts the token and returns your actual credit card details to the payment network, which are then used to authorize the transaction at your issuer bank. This is a more secure payment method because it allows you to authorize a transaction without disclosing your payment information to the merchant, payment gateway, and payment processor.

Why is all of this so complicated?

Credit cards were a tremendous innovation, but often out of reach for small businesses. For small merchants that only do limited volumes of transactions per year, or those like restaurants who only generate a little profit for every dollar they take in, credit cards were an unaffordable luxury. As recently as 2013, only 45% of the country's small businesses accepted credit cards.

Do you see that uptick in credit card payments 2009? That's when Square and Stripe were founded both focused on solving the problem of how to enable more businesses to accept credit cards. Square focused on brick-and-mortar stores and Stripe focused efforts on eCommerce. The challenges of each domain led the companies down different paths.

Before Square, a store could accept credit card payments but at a truly tremendous cost. As co-founder Jim McKelvey details in The Innovation Stack, signing up as a merchant meant stacks of indecipherable contracts, multiple different uncoordinated parties that each provided one piece of the puzzle, and truly exorbitant fees. The industry was built to service large merchants and was by-design discriminatory against smaller merchants.

Square turned the industry model on its head by bundling a payment processor (technically a payment facilitator) and payment gateway into a single service, providing it to all merchants a flat fee, and making the payment gateway so sexy that it ended up in the Museum of Modern Art.

Not only did Square's approach win business from the existing payment processors and gateways, it dramatically expanded the market of merchants who could accept payments. This same approach is what was undertaken by Stripe but for companies accepting payments over the web. The challenges are slightly different - Stripe has to solve for "card not present" because they don't get access to the physical card - but the end result is the same: over 18% of online stores use Stripe for payments.

Both Square and Stripe are in the flow of funds, a hugely advantageous position. They see every transaction a merchant processes on a per-transaction basis which enables them to offer innovative services. They can provide short-term loans to help businesses pay for inventory and analytics to predict sales. By comparing against similar merchants elsewhere, they can provide intelligence on popular products for the benefit of the merchants or to sell to manufacturers. Because of their footprint, you and I can benefit from network effects where they can offer loyalty programs and cross-sell products in novel bundles.

These startups are starting to change the playing field. That fee compression we mentioned earlier with American Express? American Express launched OptBlue once they realized that the revenue opportunity from expanding the number of merchants who accept American Express is now greater than what they can make in higher fees. OptBlue allows merchants doing up to $1 million per year in revenue to contract directly with Square and Stripe in a quasi four-party scheme where the payment processors set the fee rate instead of American Express. This is a monumental about-face for a company that's been on the same basic fee model for over 60 years.

As these startups press a competitive advantage that was previously only available to the payment networks, the networks aren't taking it lying down. Visa, American Express, and the other card associations are on the move.

Payment Networks on the Move

Many of the services mentioned above like analytics on payments and merchant lending were already part of the payment network offerings and continue to be improved. Where the networks are truly pushing the envelope is in areas where processors simply can't follow.

Apple Pay and Google Pay? They only work because the payment networks upgraded to support their new payment process involving encrypted tokens. Real-time payments, something we discussed a few weeks ago with stock trading? Visa launched real-time payments through Visa Direct in 2017 so everyone from Lyft drivers to caregivers can get paid instantly rather than waiting a day for funds.

Even more remarkable, Visa Direct is just one of over 40 services that Visa has made available to developers to integrate directly into any third party system. Mastercard has taken a similar approach. Not only does this dramatically expand the reach of these payment providers' networks, it ensures that startups like Stripe and Square always have competition that can also access the payment network services.

Cryptocurrencies are yet another battlefield. Over $1 billion was spent on goods and services in the first half of 2021 using Visa cards issued by Coinbase, Circle, and BlockFi. While a drop in the bucket of the over $2 trillion that the network processes every year, it is extraordinary growth for a payment method that essentially didn't exist 12 months ago.

Mastercard has pursued similar crypto card partnerships with Wirex and Bitpay in addition to obtaining 89 blockchain patents. Many of these are related to central bank digital currencies, a true government-issued digital currency. Mastercard even launched a sandbox environment so central banks can perform experiments with simulated digital currencies.

The future of card payments

Payments have been undergoing a rate and pace of change unseen since the card company's first burst onto the scene in the late 70s. The rise of eCommerce created a whole new economy that could not be serviced with cash and demanded card payments. Brick-and-mortar has shifted dramatically as Square rewrote the playbook for small merchants before expanding upmarket. Their innovation has launched a thousand imitators most focused on narrow verticals like the company Toast which focuses on restaurants. We didn't even get into exploring other corners of payments like the Brex corporate credit card which has rapidly penetrated the startup world.

Through all of this change that's only been accelerating for almost two decades, three trends have stood out and I expect them to continue well into the future:

Bundling and unbundling of payment services will continue. There seems to be no end to the innovative ways in which payment services can be rejiggered. Credit cards will get unbundled from banks and rebundled with neo-banks that don't actually hold banking licenses. Payment gateways will get bundled with payment processors and they will obtain banking licenses. As long as merchants are looking for better services, companies will emerge to serve them. Even a small slice of the $7 trillion card payments ecosystem is too big a prize to ignore.

Consumers and merchants will continue winning. Every time a new service is invented, consumers and merchants benefit from lower fees and new options. This is hyper-competition at its best with few to no dominant players except for the payment networks.

Payment networks are here to stay. All of this change has reinforced and often enhanced the network effects of Visa, American Express, Mastercard, and Discover. That's not to say they can sit on the laurels as competition among networks remains significant, not to mention the ever-changing landscape from Stripe, Square, and others. But the ability to hook up to a network and immediately have access to over 70 million businesses is and will remain extraordinarily valuable. That is a deep, competitive moat unlikely to be crossed soon.

It still feels like magic every time I swipe a card. Digging into the guts of the system to see how it works and finding that there's extraordinary change happening only enhances that wonder. This is a hugely exciting time for payments and one I encourage you to continue to watch closely as it evolves.

Cocktail Talk

Feeling down? Think everything is going in the wrong direction? Blame whoever was in charge in 1971. A cherrypicked but nonetheless interesting exploration of how the world has deteriorated since 1971. I'm personally attributing all of it to the decline of beef consumption (second-to-last graph).

Scientific discoveries that were always right under our noses are among my favorite. The western false asphodel, a rather pretty white flower found across Vancouver and the Pacific Northwest was recently found to be a sneaky carnivore. Its sticky stem traps small insects which it then digests to obtain a novel source of nitrogen.

DeFi, the use of cryptocurrency to build distributed financial systems, suffered its first major hack this past Tuesday. $611 million equivalent was stolen in the form of various cryptocurrencies by a hacker who exploited a bug in the code of Poly Network. The story is continuing to evolve as the hacker's stolen crypto are tracked by security firms and frozen where possible.

How'd you spend your time in 2020? Different than 2019? You're not the only one. The Bureau of Labor Statistics conducts an annual American Time Use Survey. Nathan Yau put together a helpful visualization of the comparison. I may have been an outlier - apparently everyone else was out running and did not eat and drink more.

Your Weekly Cocktail

More tiki drinks!

Shipwrecked

0.5oz Coconut Sugar Simple Syrup

0.75oz Lime Juice

0.5oz Del Maguey Vida Mezcal

1.5oz Bully Boy Rum Cooperative Volume 1

Pour everything into a shaker. Fill with ice until it tops the liquid. Shake for ~20 seconds or until the outside of the shaker is nice and frosty. Strain into a glass (a Coupe if you’ve got one) and enjoy.

I love tiki drinks. This one (with some minor modifications) comes courtesy of Sother Teague from his book I’m Just Here for the Drinks. The Shipwrecked is an unusual tiki drink in its simplicity. It trades off some of the sweetness of a classic Daiquiri (rum, lime, sugar) for the smokiness of mezcal. While it seems a small change, together with the dark rum it creates an entirely new drink. I prefer to play up the rum with coconut sugar versus the original which plays up the mezcal with agave, but you’ll be well served either way. Enjoy!

Cheers,

Jared